The Worlds of Will Edgington – NY FIGHTS – NYFights

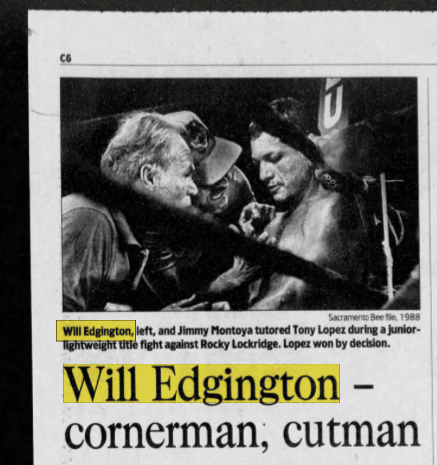

Long-time Sacramento boxing figure Will Edgington served as a matchmaker for promoter Don Chargin, owned and operated gyms, promoted fights himself, worked the corner as a cutman for many of the best Northern California fighters, and was known for years as the city’s finest trainer, working with world champions – Bobby Chacon, kickboxer Dennis Alexio, and IBF super-featherweight champion Tony Lopez – as well as contenders, also-rans, and those never-to-be.

He also served two stretches at Folsom State Prison – one as an inmate while a young man, the other as an employee, when hired in 1986 to develop and manage a boxing program for inmates at the prison. “I’m the only guy who got out of Folsom and came back with an honest job,” he would quip.

Ex inmate Will Edgington did indeed cycle back into the system upon release–but not in the usual way

Given up for adoption as an infant when his parents separated, Edgington was raised as a foster child, at first in Auburn, the foothill town about a half-hour drive east of Sacramento, and later in the Capitol city itself, where Edgington admits he fell in with the “wrong crowd.”

Edgington never saw his mother, and remembers only one brief visit with his father, at the Greyhound Depot in Auburn, where his father was a bus driver. “I remember him wiggling his watch at me,” Edgington recalls.

Fourteen when first placed in the juvenile system, an assault charge resulting from a street fight and robbery is what led to his time in prison. At eighteen, he was in San Quentin. Having begun boxing as a young teenager, he fought while in incarcerated.

Between his original sentence and those for parole violations, Edgington experienced an 11-year period in which he was a free man for only eight months.

Once out of that cycle, he was out for good, marrying and raising three children, working at first as a hod carrier and later a bartender. Edgington opened Will’s Gym at the corner of 5th and J Streets.

Fighters would come to town days before their bout, and train at Will’s as they waited for fightnight

He openly admitted that a priest and a correctional officer were responsible for his re-entry into civil society. “That was a big thing for me, that cop and that priest,” Edgington said. “He [the cop] convinced me I wasn’t what I was becoming. Somewhere down the line somebody befriends you, somebody in the system.”

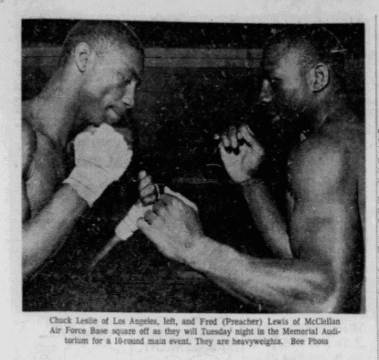

The light heavyweight Fred Roots was probably Edgington’s best fighter during this period, the 1960s, Roots’ career being turned around with Edgington’s help. He fought Bobo Olson in 1965, but, as Edgington once said to me, “Freddie wasn’t in Bobo’s class.”

Edgington stayed away from boxing for most of the 1970s, which is when his children were growing up. His daughter, Lisa, was a serious cross-country runner, and Edgington was a strong supporter of those efforts.

But he was hired as a trainer for Sal Lopez, Jr., near the end of Lopez’s career in 1982. Sal Lopez, Sr., the boxer’s father, met Edgington around 1960 at the Torch Club, where Edgington tended bar and one night became involved in an altercation with a couple of patrons.

“I was going to help him out,” Lopez said. “He was fighting two guys, you know. But he didn’t need my help so I let him alone.”

The involvement of Lopez the father with his son’s boxing was well documented, a revolving door of managers and trainers clearly compromising a once promising future. “Sal Senior hasn’t always been successful in his switches,” the Sacramento Bee’s Bill Conlin wrote.

Edgington set the conditions: “All I want is to be in charge of the corner. That’s where you sometimes win fights. Let his family make the matches, the guarantees, the percentages, but let me be in charge in the gym workouts and, most particularly, between rounds.”

Lopez the son matched well with Edgington, who was on his hiatus when Lopez turned pro in 1978, which might help to explain why the two didn’t partner earlier.

I always thought that Edgington’s withdrawal from boxing for the majority of the 1970s is a large part of the reason Herman Carter was selected as Pete Ranzany’s trainer when Ranzany began fighting professionally in 1974. I saw Edgington as a better fit for Ranzany, who might have developed a bit more under Edgington’s guidance than he did with Carter. Ranzany had beaten future welterweight champion Carlos Palomino as an amateur, but Palomino clearly improved more as a pro than did Ranzany.

The rigors of professional boxing had taken a toll on Lopez before becoming involved with Edgington, however, and he retired with an eye injury in 1983. Edgington was chosen as trainer, though, when the younger brother, Tony, a less heralded amateur than Sal, began his professional career.

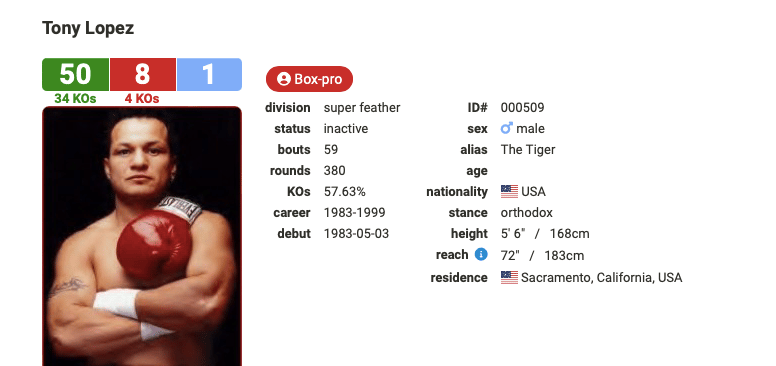

Lil bro Tony got further in the boxing game than did brother Sal

Sal Lopez was an elegant, refined boxer with good power. Tony, in contrast, had a natural inclination to fight how you might imagine a windmill would look in the middle of a tornado.

The only real difference between Tony’s first pro fight – a first round KO victory – and his amateur bouts was the fancy new satin shorts he wore once getting paid for throwing punches.

Edgington corralled that exuberance, not exactly breaking Tony, but certainly reigning in that raw, wild energy, providing a disciplined form through which Tony could intelligently, though still physically, engage his opponents. Many rounds of sparring with Bobby Chacon hardened the already naturally brave Lopez, wisening him far beyond his few months as a professional would register, convincing him that a little defense would go a long way in assisting his offense.

It was uncanny to see how Tony had learned to fight off the ropes as did Chacon, a clone developed in the laboratory of the gym. Even with all the improvement, however, most local fight observers, including me, did not expect Lopez to do as well against Rocky Lockridge as he did when defeating Lockridge for the IBF title in the fall of 1988. Lopez showed a lot of grit along with the skills he had developed with Edgington’s help.

Promoter Chargin complimented Edgington on the fight plan developed for Lopez. “It was an excellent piece of strategy,” Chargin said. “He had everybody thinking Tony was going to throw caution to the wind, even (Lou) Duva. Then he had Tony setting Lockridge up with a hammer-like left jab.”

After many years in the background, Edgington was finally receiving his due. Chacon’s trainer said of him, “[Will] is a helluva good cutman.” Edgington worked as the cutman for WBA 140-pound champion Loreto Garza and 122-pound champ Willie Jorrin, and top-ranked contender Richard Duran.

He openly admitted his years with the young Lopez were the best of his life. “This guy’s my pride and joy,” he said of Tony, so thankful that he got to plant the seed and tend to it as it grew. He had made a champion out of the raw ball of energy Lopez once was.

The former boxing commissioner of New York State and once editor of Ring Magazine, Randy Gordon, compared Edgington to the Duva boxing dynasty in New Jersey, especially the patriarch, Lou Duva. “Lopez’s trainer, Will Edgington, isn’t as well known as Duva, but he’s as good at what he does. The Duva corner is louder, but they’re no greater strategists.”

Edgington began to insert himself into some of the decision-making for Lopez that had previously been no-man’s land as far as Lopez the father was concerned. Reporters at times referred to Edgington as Lopez’s manager. Fight offers would be directed to Edgington, who said he would have to “talk with Chargin” first, not mentioning Lopez’s dad.

Rumors of Lopez being offered a large amount of money to fight Pernell Whitaker at 135 pounds were discounted by Edgington. “I’m not sure Whitaker is someone you’d want to put your fighter in against,” he said. “Any old-timer will tell you the hardest guys to fight are left-handers who run.” But this was a fight Lopez the father wanted.

Tony Lopez was tired of the struggle to make the 130-pound weight limit. He enjoyed the spoils of his success and would regularly eat himself into a middleweight between fights. Lopez thought he could handle bigger guys, but Edgington, and others, were less sure.

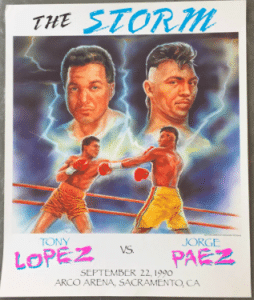

“Hell, he trained at 127 ½ pounds for the last week,” Edgington said of Lopez about his fight with Jorge Paez. The LA Forum ‘s John Beyrooty was even more to the point. “Tony should stay right where he is. If he couldn’t hurt Jorge, how’s he going to hurt a lightweight?”

Edgington thought it best if Lopez cemented his position in boxing by becoming as dominant at 130 pounds as possible. A couple of future Hall-of-Famers were competing at that weight – Azumah Nelson and Jeff Fenech. Fenech had been absolutely superb at 118 pounds, but fighting three weight divisions higher he was no longer great, just pretty good. He was, at this stage of his career, similar to what Lopez would later become after moving up a division. Edgington lobbied for Lopez to fight South Africa’s Brian Mitchell, the WBA titleholder.

Because of South Africa’s policy of apartheid, world championship boxing matches were prohibited from being held with that country’s borders, so Mitchell had become a road warrior, defending his championship on foreign turf. Fighting Mitchell would ensure that the bout take place in Lopez’s home of Sacramento, where he nearly sold out the NBA arena of the Kings.

For Lopez the father, who had come up in the world facing a situation as desperate as Edgington’s and had to become self-reliant much earlier than can be healthy, Edgington’s infringement on the control of his son could not have been comforting. “If he loses, you’re the one who did it,” Lopez told Edgington.

Being abandoned by his father before his mother died when he was only seven, Lopez, Sr., picked fruits and vegetables for a living, eventually making his way to Corona, California. Wanting more out of life than what he saw lying before him, Lopez returned to Mexico, first trying his hand at boxing, then obtaining legal papers to return to the US where he was employed in mill work and raised a family. By the time his sons were old enough to choose boxing as a career, it had been a long time since anyone made decisions on Mr. Lopez’s behalf, and that wasn’t going to change, regardless of how good Will Edgington was for Tony.

But Edgington got this wish, a fight with Brian Mitchell, who was not a powerful puncher, nor exceptionally strong, in the muscular sense. But he was the hardest working, best-conditioned athlete I have ever seen, with his cardiovascular capacity funding a work rate few could keep up with, including Tony Lopez, most noticeably in their second fight.

Mitchell’s psychological strength was extremely impressive, forged by his regularly having to travel to his opponent’s den to fight. Meeting Tony Lopez in Sacramento was a real test of that strength because Lopez was loved here and 17,000 people all in support of the same man can make a lot of noise.

Lopez drew with Mitchell in their first fight.

The fall-out, at least in the Lopez camp, began immediately. Rumors of Edgington’s imminent firing filled the gyms. Tony tried to quiet them, making statements such as, “Will’s like family…[u]ntil the day I quit boxing, Will Edgington’s going to be my trainer.”

But that tone changed within a few weeks when Edgington was dismissed. Tony said, “I appreciate what Will has done for me in the past.” The father attempted to avoid making comments, but eventually said, “I have no specific reason.” That soon altered to, “Lately, Tony hasn’t shown me that he’s been learning too much. I don’t know if it’s Tony or Will. I want to make a change to see if somebody else can help him.”

Lopez family drama, in general, was no surprise for the Sacramento boxing world – the father had successfully removed Lupe Sanchez – manager of world champion Pipino Cuevas who was showcasing young Sal on the undercards of Cuevas’ title defenses – from managerial authority.

But this move, also, made no sense to experienced observers. Chargin’s matchmaker, Sid Tenner, asked rhetorically, “After nine years you’re going to fire a guy, and you’re still champion?” Edgington, himself, was dumbfounded. “I don’t understand these people,” he said.

The Bee’s Bill Conlin, a friend of Edgington’s, wrote regularly that the explanation for the dismissal was much more simple than the complex psychological matter of control issues and power dynamics. The rematch with Mitchell was going to generate a lot of ticket sales and television revenue.

Money, the magnetic allure, that might have messed up the momentum for Edgington and Tony the Tiger

The South African government was beginning to liberalize its position on apartheid, and the boxing industry was responding to that move. Tony, the man who had fought native son Brian Mitchell to a draw, had become very marketable there, and big money fights with Mitchell and others were being negotiated.

Conlin wrote of Tony’s father that he “always has a sharp eye on the cash register.” Former world-ranked contender Stan Ward was hired as trainer, described by Conlin as “a heavyweight hanger-on who is in no position to ask for 10 percent.”

Edgington mentioned that he was owed several thousand dollars at the time of his firing, and that his customary pay – the traditional 10 percent of the fighter’s purse – had been gradually reduced as Tony’s earnings increased.

Chase Jordan was brought in for conditioning purposes, which is ironic, for Lopez was in better condition for their first fight. In the rematch, which Mitchell won by decision, the fast pace proved to be too much. About two-thirds into the fight I saw a slight hitch in Lopez’s punching rate, which reminded me of a long distance race in track-and field, say the 10,000 meters, when two runners have separated from the field and the race is between them, running at a blistering pace. There often comes a point in a match like this when one runner cannot maintain that pace and noticeably slows, with the winning runner taking a lead.

This is what happened in the second fight. Mitchell just pulled away, and Tony could not keep up.

Ward, Jordan, and assistant trainer Art Turner were gone after the loss. “I just think there is too much family involvement for us to do our jobs,” Ward said. “There was a lot of responsibility put on us, and we didn’t have the authority to carry it out.” Brother Sal Lopez, Jr., was appointed trainer.

Tony would go on to make, and spend, a lot of money, winning a couple more of the title belts that are thrown around these days. But he would never again be the boxer he was under Edgington’s guidance. He would never be in the condition he once was, making a targeted weight as he did when Edgington was in charge. He was fighting heavier, more talented people, and losing as often as he won. He made his money, but he paid for it, too, engaging in hard fights with larger, talented boxers.

He once fought as a junior middleweight, 154 pounds, and at the end was being trained by Jerry Jacobs, one of his earlier amateur coaches.

Edgington would be in and out of boxing after the dismissal, working with Ray Lovato, who once challenged Felix Trinidad for the welterweight championship, and contender Juan Lazcano. He kept his prison job for a while, which he was proud of, and eventually was staying with his daughter in Las Vegas as the end of his life neared. He died in 2005 at age 77.

He got along well with the inmates, because they knew of his past. They respected him. “I got stuck four times,” Edgington said, “three times in prison and once out,” and he had the scars to prove it.

“I was a good convict. I was a solid convict and I’m proud of that. Word leaks through the system and the guys [inmates] know that I’ve got buddies who are cops,” Edgington explained, trying to describe the inmates’ sometimes confusion of how he got along with prison administrators and guards. “When you grow up like we did, you have a distrust of the police, the [prison] officers. These guys see that I get along with them. They see me both ways. I think it’s good for them.”

Edgington was a free man for close to the last 50 years of his life, since being paroled and marrying Angie Vasquez. But there is a saying about taking the boy out of the country. Edgington had his demons, his introduction to the world certainly one of them. He and his wife losing an infant to heart disease would be another. He regularly tried to quiet those demons with alcohol, with predictably unsuccessful results.

Bill and Jeanne Barnaby, long-time family friends of the Edgington’s, married in 1956, with Angie the maid of honor. Barnaby was in the military then and the two eloped, in Barnaby’s words, because he had orders sending him to Europe and wanted Jeanne to come with him. He and his wife were surprised to find, when they returned home, that Angie had married a former convict from Folsom.

But Barnaby – not yet the prominent attorney he would become – had a lifetime of involvement in boxing, having fought as a kid and maintained friendships with pros and managers, so he and Edgington quickly fell in together. The friendship led to some memorable stories, one from the summer of 1965, when Fred Roots fought Aristeo Chavarin. Barnaby was about to enter Memorial Auditorium to watch that evening’s bouts when he saw Edgington in a torn T-shirt – bruised , battered, and bleeding – rushing to meet Roots in the dressing room.

Edgington had a rep as a man’s man.

Edgington had, the night before, gotten into a fight at the V&F Club, which was across the street from the gym and about a block away from the police station. Patrolman Harold Hinton tried to break up the fight when Edgington began punching him. Calling for re-enforcements, Edgington fought off multiple officers until finally being subdued and carried to jail. Edgington told Barnaby that he was in such poor condition because when the police had him in custody at the station they put him in an elevator and “beat the shit out of me.”

He made bail just in time for the Roots fight, which Barnaby remembers as one of Roots’ better efforts.

Edgington and his wife separated after their children were grown, early in Tony Lopez’s career. Angie was shot and killed by a man she had been seeing, later described as someone who became angry when women broke up with him. Allen Willis would plead no contest to a reduced charge of involuntary manslaughter.

“My dream…is to help kids not become convicts and help convicts out and have kids,” Edgington once told a Bee reporter, explaining the larger reason for his job. “I know it’s not going to work for everybody.”