From the Archive: 1992 Ferrari 512TR Epic Cross-Country Road Trip – Car and Driver

From the August 1992 issue of Car and Driver.

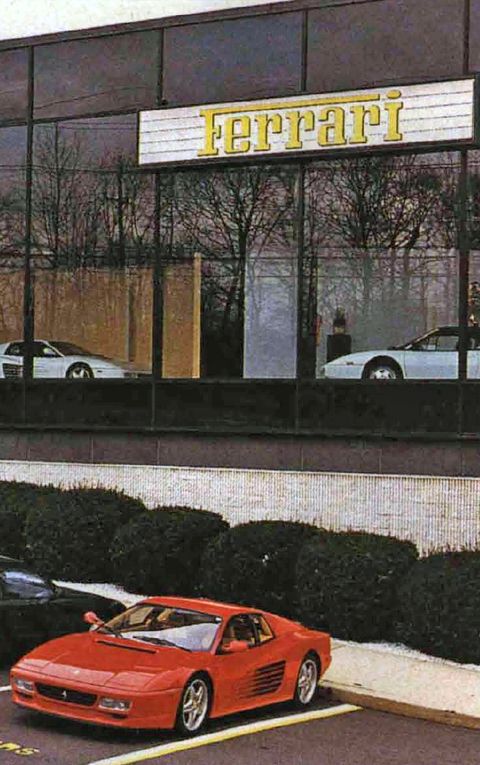

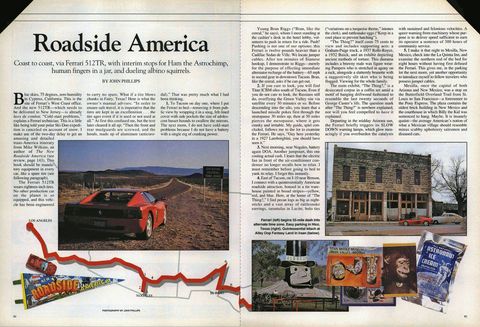

Blue skies, 75 degrees, zero humidity in Cypress, California. This is the site of Ferrari’s West Coast office. And the new 512TR—which needs to be delivered to New Jersey—is already hors de combat. “Cold-start problems,” explains a Ferrari technician. This is a little like being told your polar Ski-Doo expedition is canceled on account of snow. I make use of the two-day delay to get an amusing and detailed trans-America itinerary from Mike Wilkins, an author of The New Roadside America. This book should be mandatory equipment in every car, like a spare tire (see following paragraph).

The Ferrari 512TR wears eighteen-inch tires. No other production car on the planet is so equipped, and this vehicle has been engineered to carry no spare. What if a tire blows chunks in Fairy, Texas? Here is what the owner’s manual advises: “In order to ensure safe travel, it is imperative that the tires are kept in an excellenition…the tire ages event if it is used or not used at all.” At first this confused me, but the text later cleared it all up: “Then the front and rear mudguards are screwed, and the hoods, made up of aluminum (anticorodal).” That was pretty much what I had been thinking.

One

To Tucson on day one, where I put the Ferrari to bed—removing it from public view by wrapping it in a snug, felt-lined cover with side pockets the size of adolescent basset hounds to swallow the mirrors. The next morn, I do not have cold-start problems because I do not have a battery with a single erg of cranking power.

Young Bran Riggs (“Bran, like the cereal,” he says), whom I meet standing at the cashier’s desk in the hotel lobby, volunteers to push in return for a ride. Push? Pushing is not one of our options: this Ferrari is twelve pounds heavier than a Cadillac Sedan de Ville. We locate jumper cables. After ten minutes of Siamese hookup, I demonstrate to Riggs—merely for the purpose of effecting immediate alternator recharge of the battery—65 mph in second gear in downtown Tucson. Bran, like the cereal, asks if he can get out.

Two

If you care to look, you will find a Titan ICBM silo south of Tucson. Even if you do not care to look, the Russians still do, overflying the Green Valley site via satellite every 30 minutes or so. Before descending into the silo, you learn that a launched missile pokes first through the stratopause 30 miles up, then at 50 miles pierces the mesopause, where it gets cranky and irritable. My guide, spiel concluded, follows me to the lot to examine the Ferrari. He says, “Guy here yesterday in a 1927 Lamborghini, you should have seen it.”

Three

Next morning, near Nogales, battery again DOA. Another jumpstart, this one costing actual cash. I learn that the electric fan in front of the air-conditioner condenser no longer recalls how to relax. I must remember before going to bed to yank its relay. I forget this instantly.

Four

East of Tucson, on I-10 near Benson, I connect with a quintessentially American roadside attraction, housed in a tin warehouse painted in broad stripes—yellow, red, and blue. Here, at the home of “The Thing?,” I find pecan logs as big as nightsticks and a vast array of rattlesnake earrings, tarantulas in Lucite, bolo ties (“variations on a turquoise theme,” intones the clerk), and rattlesnake eggs (“Keep in a cool place to prevent hatching”).

“The Thing?” itself costs 75 cents to view and includes supporting acts: a Graham-Paige truck, a 1937 Rolls-Royce, a 1932 Buick, and an exhibit depicting ancient methods of torture. This diorama includes a brawny male wax figure wearing Pampers who is stretched in agony on a rack, alongside a slatternly brunette with a suggestively slit skirt who is being flogged. Viewing for the whole family.

The main exhibit, “The Thing?,” is a desiccated corpse in a coffin set amid a motif of hanging driftwood fashioned to resemble the last twenty seconds of George Custer’s life. The question mark after “The Thing?” is nowhere explained, nor will you feel compelled to have it explained.

Departing in the midday Arizona sun, the Ferrari briefly triggers its SLOW DOWN warning lamps, which glow menacingly if you overburden the catalysts with sustained and felonious velocities. A queer warning from machinery whose purpose is to deliver speed sufficient to earn its operator a sentence of 300 hours of community service.

Five

I make it that night to Mesilla, New Mexico, check into the La Quinta Inn, and examine the northern end of the bed for eight hours without having first defused the Ferrari. This gives me, in the parking lot the next morn, yet another opportunity to introduce myself to fellow travelers who possess jumper cables.

Mesilla, once the capital of both Arizona and New Mexico, was a stop on the Butterfield Overland Trail from St. Louis to San Francisco—a forerunner to the Pony Express. The plaza contains the oldest brick building in New Mexico and the courthouse in which Billy the Kid was sentenced to hang. Maybe. It is insanely quaint—the average American’s notion of what a Mexican village should resemble minus scabby upholstery salesmen and diseased cats.

Six

Head north from Las Cruces on Route 70 through the middle of the White Sands Missile Range (where the army often stops traffic for fear something seeking heat might seek it in the engine bay of Aunt Ethel’s Winnebago) and you land on the steps of the International Space Hall of Fame, in Alamogordo. Visit the burial site of Ham the Astrochimp, a fetching primate who uneventfully but quite involuntarily plunged through the mesopause himself in 1961. A fiberglass replica of Ham suggests his legs were severed and he was fitted with Howard Cosell’s hairpiece.

It is in Alamogordo that one of the burning issues of our time has been wrestled to Earth’s crust: How, exactly, does one boldly go where no man has gone before? On display here is the answer, a Skylab commode, complete with instructions: “Pulling up gate valve control activate slinger motor…slinger tines shred feces and deposit it in thin layer on commode walls.” This sounds pretty much what I might have done if, like Ham, I had been plunged moonward without consent. It also explains the NASA pejorative, “You are a slinger.”

Seven

At the Texas border, the 512TR and I grimace through a body-shuddering crow impact, this despite the car’s heavy but precise steering, which is much like that in an Acura NSX. I jinked to miss what this football-size scavenger was eating—looked like javelina entrails—and the crow jinked to miss the incoming red Ferrari. Self-canceling jinks. I stop. There is no sign of the Ferrari’s AC condenser having eaten crow, although there is a fairly complete and graphic display of javelina gastrointestinal subassemblies in the right-front wheel well. I skip looking in there too closely, on the theory that a 140-mph burst will deliver a ground-effects cleansing.

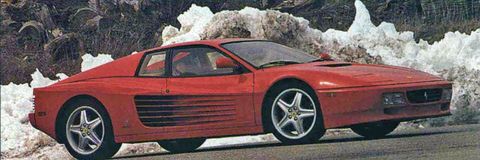

It does. And it gives me cause to listen to the Ferrari achieve its 7300-rpm redline in four gears. As Joe Bob Briggs says, “We are talking serious chop sockey, here.” The 512TR produces 421 hp at 6750 rpm, a 41-hp increase over the TR it replaces, thanks largely to higher-compression pistons.

The new car punches through the quarter-mile in 13.0 seconds at 110 mph, versus the old TR’s 13.3 at 107. From dead rest to 60 mph requires five seconds flat—no improvement. If you keep track of such things, that is 0.6 second longer than required by a Lamborghini Diablo or a Porsche 911 Turbo. The 512TR could probably crack off consistent 4.8-second 0-to-60 sprints (the acceleration the factory asserts, in fact) were it not for the lolly-gagging you must invest in the byzantine upshift to second gear. Ferrari cannot bear to part with the anachronistic plastic eight-ball shift knob, held skyward at the tip of a spindly metal pole that juts out of a hedge-trimmer maze of aluminum teeth and gates.

The 512TR now fetches $212,160. This is without a radio. This is without a spare. This is $84,000 more than I owe for my home, although an ex-sewage commissioner’s house will not circulate a skidpad at 0.92 g (more grip than a 911 Turbo) without kitchen cutlery flying out of drawers.

Eight

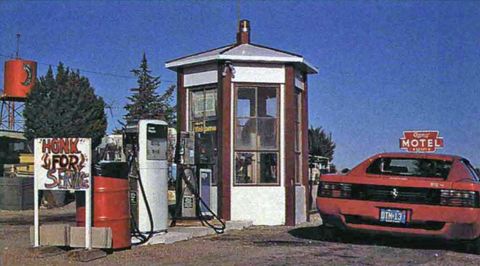

East of El Paso on Route 62/180, is Comudas, Texas, population “five or six.” A motel, two working gas pumps, and a cafe. That is all. A time warp, a Scorsese movie set. The outdoor restrooms are next to a garden prominently posted, “Keep out of cactus,” suggesting that tourists daily frolic pantsless in the spiny ocotillo.

Nine

Route 62/180 is one of Texas’s great. straight, unmolested country two-lanes, shadowed by buttes and mesas and purple table-top hummocks that lead an ever-upward march to Guadalupe Peak at 8751 feet—the highest point in Texas. In this region raged the El Paso Salt War of 1877. I aim south on Route 54, along kelly-green edges are few traces of civilization and whose 55-mile length the Ferrari and I traverse in, it looks like 20 minutes, at an average clip of 4500 rpm in fifth gear, the speedometer having been painstakingly positioned so that its operator will not be distracted by the digits between 40 and 120 mph.

Here the Ferrari and I enter the Central Time Zone at a speed that might convert more readily to Greenwich Mean Time. And here I find the sort of driving and scenery that cause men to abandon their Franklin Planners to stare doe-eyed at roadhouse waitresses named Winona Rae.

Ten

Then back to the real world. At the end of Route 54 and the intersection of I-10 is Van Horn, Texas, a place with all the charm of Sam Kinison’s car wreck. Darkness is falling. I take what is intended to be an hour-long nap, wrapping myself mummy-style in the Ferrari’s Gore-Tex cover. I awake not 60 minutes later but seven hours later in an Olympic sweat as the Texas sun uncorks an unignorable solar broadside. I am more or less left crippled by this experience, but it seems probable that I emerge the first sentient being to spend a wholly wakeless night in a Ferrari 512TR. (Fine, write Ed. if you’ve already done it.)

That I could even daydream in this car, never mind sleep, says something about its spaciousness. This is no optical illusion. The 512TR is 3.5 inches wider than Mercedes’s beefiest megacruiser, the 600SEL. It also says something about the seats, which are among the world’s most comfortable for twelve-hour days of potentially weary wheelwork. These seats are as pliable as an armadillo, and they offer only two adjustments. Just like the seats in the Acura NSX, which are possibly the best in the known universe. There is a lesson here.

Eleven

In the Fort Stockton, Texas, cemetery, a few yards from Paisano Pete (world’s largest roadrunner), lie the remains of Sheriff A.J. Royal, who, like another A.J. from this very state, ran his affairs with sufficient lone-star bullheadedness that veins in the foreheads of most townsfolk began to bulge. Six locals met secretly in November 1894 to draw beans (no straws available), and the sheriff shortly thereafter showed up for work one morning fatally and seriously dead. Bad luck, but it did earn A.J. a tomb tone—a surpassing rarity in those days—on whose face remains the as-yet-uneroded epitaph, “Assassinated.”

Twelve

Head east on I-10 and a little north through brown, scrubby Texas Hill Country and you find Iraan, just a few miles past a sign that says, “Caution, poison gas produced in this area.” Like the real Iran.

Iraan is home to the Marathon Oil Discovery well, tapped in 1926 by I.C. Yates, a revelation that encouraged the great Texas oil boom. Yates (most likely kin to Assassin Brock) had never heard of a country called Iran. He simply invented the town’s label by combining his first name, Ira, and his wife’s, Ann. He might have withdrawn that familial contraction had he known that Iraan would later be better known as the birthplace of the Alley Oop comic strip-now commemorated by Kenworth-size concrete likenesses of Mr. Oop and “Dinny, his pet dinosaure [sic],” which someone has evidently erected without permission in the town park.

Thirteen

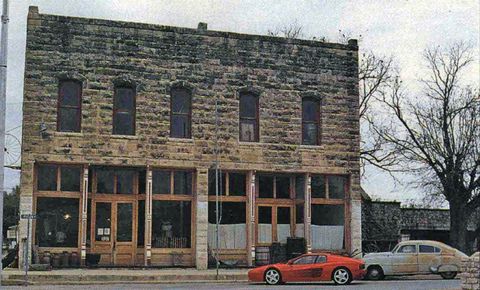

Blaze 225 miles east to the Buckhorn Museum, appropriately attached to the Lone Star Brewery. Here is how to find it: Drive to that section of San Antonio where Monte Carlo lowriders cruise not with vinyl but with shag carpeting glued to their roofs. The Buckhorn Museum features an extensive collection of stuffed animals with an expansive range of deformities—an elk with “freak antler growth,” a “deer with diseased antler,” lamps made of deer limbs, a tribute to “a totally blind hunter,” and a squirrel permanently coiled in its most deadly poised-to-strike pose, just moments before a Texan gunned it into segments so minute that only a veteran taxidermist could reassemble the rodent, using extensive diagrams and drawings.

To be fair, the Buckhorn Museum is not all antlers. It includes the Hall of Fins and the History of Barbed Wire, although I bypass both when a Baptist school bus disgorges 30 third-graders next to the Ferrari, into whose right-door lock one enterprising young Baptist is urgently wedging an impressive quantity of Gummy Bears.

By the fifth day, I am exasperated by the attention the Ferrari draws. Knots of gawkers during refueling. Mini riots on the main streets of villages, where one cop asks, “You planning to move soon, cause there’s going to be a wreck or something.”

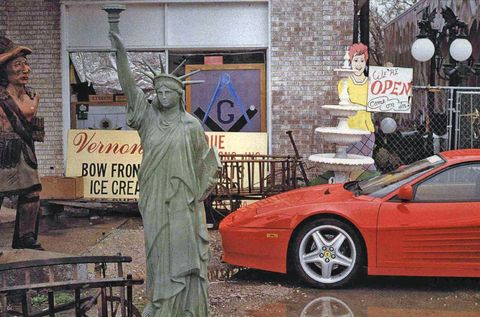

North of San Antonio, exiting Interstate 35 for a rest, I am followed by two onlookers whose cars flank the Ferrari like pilot fish. Both drivers get out and follow me into the restroom. They deliver rapid-fire interrogation as I stand before the urinal. “How much?” “How fast?” “Where you headed?” “How’d you get this job?” As I exit the outhouse—walking briskly past a stallion that a cowboy is leading through the pet-exercise area—a bystander blurts, “How much do you make?”

By the sixth morning, I learn to wrap the car in its cover within 120 seconds of arrival in any parking lot. Driving a 512TR affords a grim glimpse of what it is like to have a celebrity’s face. Being seen in this Ferrari fast wears surpassingly thin, whereas driving the car fast never does.

Fourteen

Seguin, Texas: world’s largest pecan, on a pedestal in the town square. A plaque in front of this refrigerator-size, 1000-pound nut reads: “Cabeza de Vaca traveled the River of Nuts. He…had ample opportunity to observe the growth and fruiting habits of pecans…the first recorded contribution to the pecan literature.” I am not notably low on pecan literature.

Fifteen

From Seguin, it is but a short drive to the snake farm at the Engels Road exit off I-35, just south of New Braunfels. Here, for $4.98, you may purchase “Pure, unadulterated 100-percent genuine bull shit.” Other highlights: a deep rattlesnake pit with an excellent assortment of cockroaches—next to a machine that measures your heart rate for 25 cents-and a two-headed monkey corpse under glass.

From which you may want to drive to McDonald’s, where, for the third time, just as I enunciate my order into the drive-thru clown’s head, the 512TR’s water hits 195 degrees, triggering the side-mounted fans. This sounds like a Husqvarna chain saw in a pay toilet—a racket that reliably causes McDonald’s servers to shout, possibly as many as five times, “What?”

Sixteen

As it happens, the 60-mile stretch of I-35 between San Antonio and Austin is awash in grade-A tourist effluvia, most of it superior to the Dan Blocker Memorial Head (Hoss’s head, not a commemorative marine lavatory) in O’Donnell, Texas, Check out Topsy Turvy World (“the antigravity world”), Dinosaur Land, Wonder World (“see an earthquake from the inside out”), Vasectomy Reversal (“money-back guarantee”), Luby’s Cafeteria (site of the Killeen massacre and a potential installment of Wilkins’s Doom Tour), and Aquarena Springs, whose diving pig Ralph swims with a palsied dog paddle that proves him traitorous to a dozen performing porcine predecessors.

Seventeen

Glen Rose, southwest of Fort Worth: a Norman Rockwell village filled with persons who entrust their savings to the Cow Pasture Bank, “home-owned and operated since 1921.” The Ferrari triggers a festival here. One onlooker observes that to spend $212,160 on any car, “you have to be dumb as fungus, dumb as an acre of mud.” It did not help that, as I entered Glen Rose, I maintained the 512TR’s flat twelve at about 5500 rpm in first gear—this to enjoy the Valkyrian exhaust shriek. Which, it turns out, is not a sound that Glen Rose’s residents want to learn very much more about.

Glen Rose is famous for its dinosaur tracks. Three kinds: acrocanthosaurus (a meat eater), camptosaurus (a plant eater), and pleurocoelus (a tobacco chewer and phlegm dislodger). A lone track on display next to the town square is, on the day I visit, filled with chocolate milk.

Check out the Creation Evidences Museum, where you may examine “humanoid footprints” in the same strata as thunderlizards. This, according to the owner, emphatically junks Chuck Darwin’s shot at any more of those one-hour specials on the Discovery Channel.

Eighteen

Durant, Oklahoma, home of the world’s largest peanut. Wilkins insists this is “a fraud among nuts, mere peanuts envy.” The world’s most gargantuan goober—nine feet longer—is in Ashburn, Georgia.

Oklahoma’s Route 69—chunks of concrete arrayed randomly by the ODOT—was not designed for a 512TR with tires whose sidewalls flex with the elasticity of Scioto limestone. The Ferrari’s ride is sharp, often harsh—like a Corvette’s from a few year ago—but with far less body shake and flex. The inch or so the springs seem to deflect for these Oklahoman craters also feels like the sum total of body movement, no matter the direction. The car corners in an attitude so flat, and the seats grip so firmly, that astounding cornering forces sneak up unannounced, like Dan Quayle on a PGA tournament. My first clue: that bag of Doritos and the telephoto lens that went hurtling from the passenger’s seat with momentum sufficient to imprint Nikon’s logo in the kick panel.

Nineteen

Wilkins’s itinerary lands me in hardscrabble Commerce, Oklahoma, peculiarly named because there is no evidence it has ever had any. This is Mickey Mantle’s home town; few residents care. Mantle sold his modest yellow house, across from the football field, in 1960, but the current owner still speaks to Mickey when he isn’t making guest appearances on the shopping channel.

Twenty

A few miles north is West Mineral, Kansas, where you cannot help but observe Big Brutus, the world’s second-largest electric shovel. It resembles the current crop of electric cars: eleven million pounds, maximum speed of 0.2 mph. The shovel’s owners permanently parked this rusting colossus in a strip pit that Brutus himself dug—this after examining an invoice that proved the thing had consumed $27,000 of electricity in just one month while still attached to the world’s thickest extension cord. This is unfortunately unlike electric cars, which cannot dig the pits in which they may similarly play out eternity.

Twenty-One

In Carthage, Missouri, Wilkins cites the Precious Moments Chapel as “a mandatory stop, one of our seven wonders.” The Chapel here is one-third Franciscan monastery, one-third Six Flags over Jesus, and one-third Fairview Mall. Imagine the outcome had the Sistine Chapel been adorned not with murals of Moses but with a clump of black-eyed dead babies loitering at the gates of heaven, each painted by a Disney animator on furlough from Hallmark Cards. Remarks Wilkins, “Is it art, or is it spiritual Nutrasweet, not only fake but containing something that when taken in large doses makes you stupid?”

Twenty-Two

Past Saint Louis and the Pro Bowling Hall of Fame and into Olney, Illinois (pronounced ALL-nay). This is one of three towns vying for the title of Earth’s epicenter of albino squirrels, which, I am four times reminded, “scientists are at a loss to explain.” Townspeople are militant about this, pointing out that squirrels in rivaling Marionville, Indiana, and Kenton, Tennessee, “are pure fakes, because, look, they just don’t all have pink eyes, so they’re nothing except squirrels with white coats, okay?” An Olney patrolman parked next to me informs: “Squirrels have the right-of-way in town. It’s a $25 fine if you run over one. Also, I can arrest you if you take one.” I subdue the impulse.

Twenty-Three

John Dillinger Wax Museum, in Nashville, Indiana. Near Gnaw Bone. Focal point: a replica of J.D.’s bullet-riddled body laid out on a slab, the whole tableau awash in red dye No. 3. “Many angles are offered for your viewing pleasure,” notes Wilkins. Entry includes a peek at “Dillinger’s death trousers” (contents of his pockets on view as well) and his baseball shoe (no clear explanation for this).

Twenty-Four

Next, Honda’s test track near Marysville, Ohio, where we learn that the 512TR will indeed poke its way through many portions of its speedometer I have not yet seen. Top speed is not 192 mph as advertised but a still-inspiring 187—an improvement over the 173- and 176-mph speeds we have clocked from previous Testarossas.

It is also here that we test the 512TR’s new Brembo calipers and drilled rotors, which look so raffish that owners may not care whether they arrest motion. In fact, they do. From 70 mph, this car now halts in 169 feet. That is without ABS. That is a stopping distance within 36 inches of what a 911 Turbo can accomplish with ABS.

Twenty-Five

Swing past the Wood County Historical Museum, on Route 6 near Bowling Green. Here are stored dried human fingers in a jar, the long-forgotten evidence in a criminal prosecution but an eminently unforgettable spectacle should you later purchase french fries at the Mt. Victory Union 76.

Twenty-Six

Quick stop in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, for Phil the groundhog, whose forecasts are now challenged by an equally moody rodent in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. Which town possesses the more reliable ‘hog meteorologist triggered a debate in Congress on a day when many legislators were not balancing their checkbooks. The town’s basketball team is known as “The Chucks.”

Twenty-Seven

This is followed by an even briefer stop in Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, formerly known as Mauch Chunk, suggesting that the name change was perhaps not a notably controversial item. In town, the Olympic great’s pink-marble mausoleum lures few tourists. “Mute testament to greed untempered by market research,” says Wilkins.

Twenty-Eight

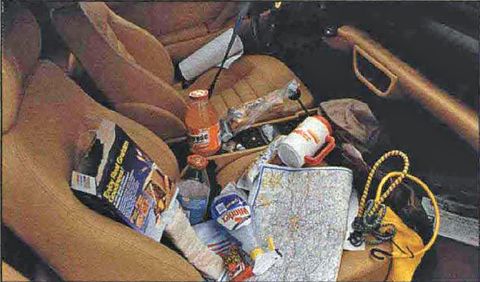

Then into Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, the 512TR ‘s home and a locale whose roads—evidently shipped intact from Beirut—and Third World drivers place the car in far greater jeopardy than it has faced in the preceding 5000 miles, except for the night I slept in it after consuming two tacos, a granola bar, twelve ounces of Switzer’s licorice, and a quart of orange Gatorade.

All of which teaches us, well, what? I went looking for U-Will-B-Amazed kitsch and instead found charm and adventure and endless entertainment, most of it nearly free except for $421 in fuel and $35.95 in jumpstarts and $212,160 for wheels but no spare. I found that America’s small towns are not only alive and well but also populated by persons who know whose checks are good and whose wives are not. That those same small towns are not populated exclusively by the humor-impaired. And that the tackiest and most banal roadside attractions in middle America are more engrossing than the brightest and best on network television.

If I owned this 512TR—the first Ferrari that I covet beyond measure—I would stuff its map pockets full of No-Doz and The New Roadside America, cancel my subscription to Discover magazine (May cover: “Why are pygmies small?”), and pawn my big-screen RCA.

In his book Blue Highways, William Least Heat Moon says, “Any traveler who misses the journey misses about all he’s going to get.” Mr. Moon did not even own a Ferrari. He did, however, possess a spare tire.

Specifications

Specifications

1992 Ferrari 512TR

Vehicle Type: mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive, 2-passenger, 2-door coupe

PRICE

Base/As Tested: $212,160/$212,160

ENGINE

DOHC 48-valve flat-12, aluminum block and head, port fuel injection

Displacement: 302 in3, 4943 cm3

Power: 421 hp @ 6750 rpm

Torque: 360 lb-ft @ 5500 rpm

TRANSMISSION[S]

5-speed manual

CHASSIS

Suspension, F/R: control arms/control arms

Brakes, F/R: 12.4-in vented disc/12.2-in vented disc

Tires: Pirelli P Zero

F: 235/40ZR-18

R: 295/35ZR-18

DIMENSIONS

Wheelbase: 100.4 in

Length: 176.4 in

Width: 77.8 in

Height: 44.7 in

Passenger Volume: 47 ft3

Trunk Volume: 5 ft3

Curb Weight: 3684 lb

C/D TEST RESULTS

60 mph: 5.0 sec

100 mph: 10.3 sec

1/4-Mile: 13.0 sec @ 110 mph

130 mph: 17.7 sec

150 mph: 26.3 sec

Rolling Start, 5–60 mph: 5.5 sec

Top Gear, 30–50 mph: 6.6 sec

Top Gear, 50–70 mph: 7.0 sec

Top Speed: 187 mph

Braking, 70–0 mph: 169 ft

Roadholding, 300-ft Skidpad: 0.92 g

C/D FUEL ECONOMY

Observed: 16 mpg

EPA FUEL ECONOMY

City/Highway: 11/16 mpg

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.