Why Escapism Benefits Some Recreational Runners but Not All – Psychology Today

Why Escapism Benefits Some Recreational Runners but Not All Psychology Today

Ground Picture/Shutterstock

Escapism is marked by “a habitual diversion of the mind.” Every day, it gives millions of us much-needed distraction from the monotony of the daily grind. The Cambridge Dictionary defines escapism as “a way of avoiding an unpleasant or boring life.”

Frode Stenseng of the University of Oslo and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology created a two-dimensional model of escapism consisting of self-expansion (adaptive escapism) or self-suppression (maladaptive escapism).

Subjective well-being questionnaires are often used to rate levels of happiness and life satisfaction. Accumulating evidence suggests that when escapism is rooted in self-expansion, people tend to be happier and more content.

Escapism Is a Doubled-Edged Sword With Pros and Cons

Stenseng’s dualistic approach to escapism suggests that people’s motivation to “escape the self” by engaging in a particular activity can be driven by a mindset of striving to experience positive emotions (self-expansion) or avoiding negative feelings (self-suppression).

Adaptive and maladaptive escapism stem from two different mindsets:

- Promote a positive mood (Adaptive/Self-expansion escapism)

- Prevent a negative mood (Maladaptive/Self-suppression escapism)

In the paper, “Activity Engagement as Escape From Self: The Role of Self-Suppression and Self-Expansion,” Stenseng and colleagues introduced a scale for measuring people’s intentional mindset when seeking escapism during leisure activity engagement. According to the authors, this paper “introduces escapism as a relevant theoretical and empirical concept applicable to several types of activity engagements.”

Over a decade later, in a follow-up paper, the researchers applied their two-dimensional model of escapism to recreational running. Their findings (Stenseng et al., 2023) on how two types of escapism influence subjective well-being and exercise dependence among 227 recreational runners were recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Frontiers in Psychology.

First and foremost, the researchers’ analysis showed that “the escapism dimensions were highly diversifiable among this sample of recreational runners.”

That said, on average, correlational analyses showed that among recreational runners, “self-expansion was positively correlated to subjective well-being, whereas self-suppression was negatively related to well-being.” Additionally, a self-suppression mindset was more strongly linked to exercise dependence, but people who scored higher on self-expansion were also prone to exercise addiction.

Adaptive Escapism Can Boost Subjective Well-Being; Maladaptive Escapism Can Lower It

Overall, the Norwegian researchers found that among runners prone to maladaptive escapism, self-suppression was more strongly correlated with avoidance coping, typically characterized by procrastination and other attempts to avoid problems.

On the flip side, those motivated by self-expansion and a desire to promote positive emotions during a run tended to experience more long-term psychological benefits from physical activity. They also tended to have an approach-oriented coping style rooted in acknowledging challenges and trying to resolve them proactively.

As the authors explain, “[Self-expansion] motivation is related to more harmonious passion; that is, an interest in an activity that nourishes one’s subjective well-being. It has also been shown to be associated with more flow experiences in the activity, compared to self-suppression.”

“More studies using longitudinal research designs are necessary to unravel more of the motivational dynamics and outcomes in escapism,” Stenseng concluded in a January 2023 news release. “But these findings may enlighten people in understanding their own motivation and be used for therapeutic reasons for individuals striving with a maladaptive engagement in their activity.”

My Experience as a Runner Reaffirms Findings on Escapism’s Doubled-Edged Sword

In a recent post on teenage depression, I discussed how my motivation to start running as a 17-year-old in the summer of 1983 was sparked by the passionate mindset of Jennifer Beals’ character in Flashdance and the movie’s theme song. Armed with a pair of headphones, I was able to relive the escapism of that movie every time I heard Irene Cara sing “Flashdance, What a Feeling” on my Walkman while doing a 30-minute daily jog.

As a runner and gay teen in the early ’80s, I was a happy-go-lucky free spirit. Before the AIDS pandemic started decimating people in my community, I didn’t feel the need to escape my daily life via self-suppression while running. In a pre-HIV AIDS world, my daily runs were filled with joie de vivre and lots of self-expansion, not self-suppression.

That all changed by the mid-1980s when HIV-positive people in my neighborhood started getting sick and dying en masse. At the time, I was living in Manhattan’s West Village, a few blocks north of Christopher Street near St. Vincent’s Hospital.

As I watched people close to me wasting away, running became an avoidance coping mechanism. It also sublimated my libido. Even safe sex was a terrifying prospect at the time. Training and competing in marathons became a substitute for having intimate relationships in a way that wasn’t healthy.

Throughout the late ’80s, my exercise dependence was off the charts. My motivation to run farther and faster was primarily driven by an obsessive need to escape the pain of day-to-day life via extreme amounts of exercise.

By 1990, I realized that my exercise compulsion was a problem and got help from a psychoanalyst at the White Institute. Around the same time, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi was published.

Source: Duppydupdup/Shutterstock

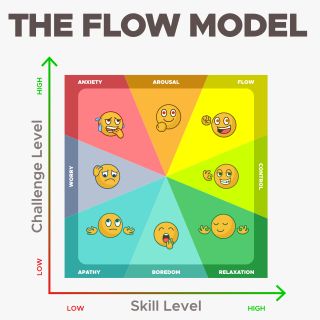

Learning about “The Flow Model” altered my escapism mindset. Instead of exercising to escape life and prevent a negative mood by running away from something, my motivation flipped to pursuing flow and running towards flow state experiences, which are associated with self-expansion escapism.

In the mid-1990s, I started competing in Ironman triathlons and got a sponsor that paid me to do international races. Once running, biking, and swimming became a 9-to-5 job, its ability to provide escapism evaporated, which created an existential crisis.

Also, during this period, I spent an excessive amount of time every day in what Csikszentmihalyi calls the “Flow Channel,” a sweet spot where one’s degree of skill and the level of challenge is perfectly matched. Unfortunately, being in the Flow Channel began to feel like being stuck in a rut, and my flow state experiences became mundane. Flow had lost its “Wow!” factor, which was dispiriting.

Luckily, through trial and error, I realized that if I upped the level of challenge in a way that made triathlon training seem less monotonous and more adventurous, it created a mindset shift that facilitated episodic bursts of what I call superfluidity. The frictionless flow of superfluidity is self-expansive and promotes blissful moments of sublime escapism.

Throughout the early 2000s, my pursuit of superfluidity motivated me as an ultra-marathoner. Because my motivation as an extreme-distance runner was rooted in self-expansion and adaptive escapism, I didn’t ever feel burned out, and my subjective well-being was robust. Nevertheless, if tested, I’m sure I would have scored high for “exercise dependence” during this period.

In 2004, after breaking a Guinness World Record by running six back-to-back marathons in 24 hours, I retired from competitive sports and have been a recreational runner ever since.

Even before learning about Stenseng’s two-dimensional escapism framework, as a recreational runner, I know from first-hand experience that being motivated by self-expansion (not self-suppression) makes my daily jogs feel like they come from a place of “harmonious passion.”

Hopefully, learning about the upside of being motivated by self-expansion and the pitfalls of self-suppression escapism will help other recreational runners lower their odds of debilitating exercise dependence while boosting subjective well-being.