How Elite Runners Train When They’re Pregnant – Outside

Outside’s long reads email newsletter features our strongest writing, most ambitious reporting, and award-winning storytelling about the outdoors. Sign up today.

When Elle Purrier St. Pierre, the 27-year-old Olympic miler and multiple American record-holder, announced her pregnancy a few weeks ago, fans were surprised. I was too, even though I recently wrote about a study suggesting that pregnancy doesn’t alter the career trajectory of elite runners. Old habits die hard, and the knee-jerk assumption that motherhood will derail an athlete’s career remains deeply entrenched—which makes another newly published study about the impact of pregnancy on training and performance in elite runners all the more important.

A team of researchers in Canada led by Francine Darroch of Carleton University in Ottawa and Trent Stellingwerff of the Canadian Sport Institute Pacific recruited 42 elite distance runners, more than half of whom had competed at the Olympics or World Championships at distances ranging from 1,500 meters to the marathon. Using their training logs, the runners reported how their training changed before, during, and after their first pregnancy, which occurred at ages ranging from 20 to 42 years old. The researchers also analyzed how their publicly available competition results changed.

The results, published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, should be reassuring to Purrier St. Pierre’s fans. Among the runners who reported intending to return to the highest levels of competition after their pregnancy, there was no significant difference between their pre- and post-pregnancy race times. Roughly half of them got better and half of them got worse, which in the world of elite sport is pretty decent odds.

That’s great news, but even more illuminating is the detailed training data the athletes shared. Experts are understandably cautious about giving advice to women who are accustomed to very high levels of exercise and wish to maintain those levels during pregnancy. All the women in Darroch’s study had safe and successful deliveries. We shouldn’t read too much into that, because women who didn’t probably wouldn’t have signed up for the questionnaire-based study. Still, the training data offers some real-world context from athletes who trained through successful pregnancies.

The data looks at five key timepoints: a year before pregnancy, during the first, second, and third trimesters, and a year after pregnancy. Overall, they kept running a similar number of days throughout pregnancy (6, 6, and 5 in the three trimesters), but gradually shortened the duration of runs and sharply reduced the number of medium- and high-intensity runs.

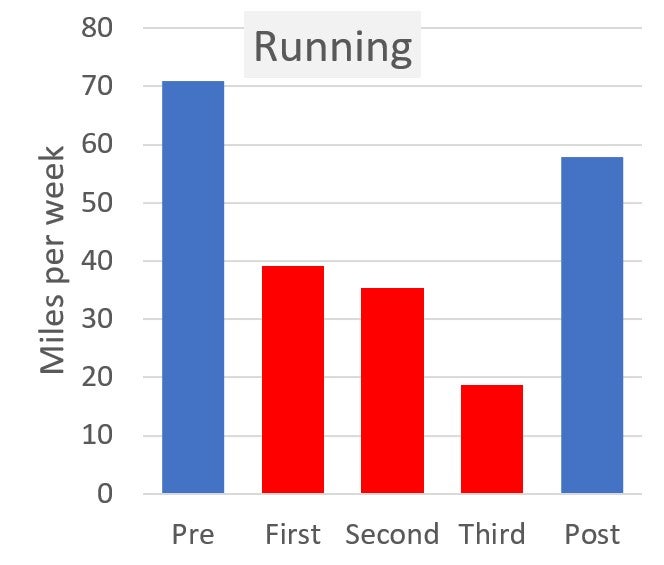

Here’s their average mileage at those five timepoints:

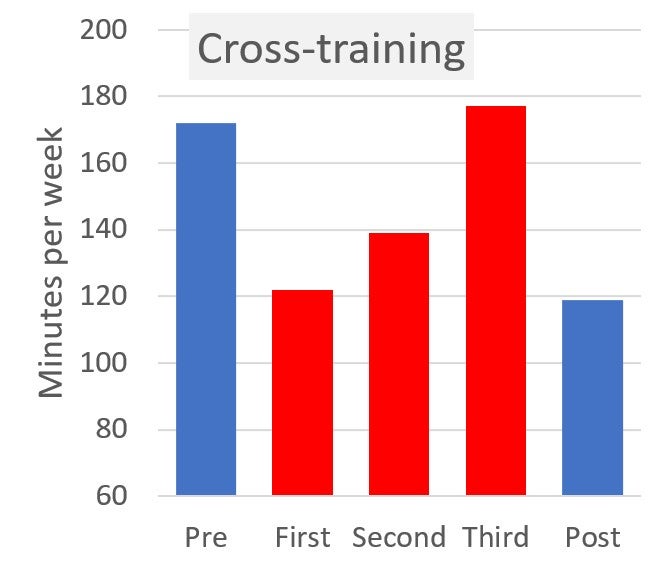

In parallel, they ramped up cross-training, presumably to lower-impact activities like elliptical or swimming, so that total training time remained similar. Here’s how that evolved:

After pregnancy, the women waited on average three weeks before resuming cross-training, and six weeks before resuming running, albeit with substantial individual variability. They were back to roughly 80 percent of pre-pregnancy training levels by 14 weeks post-delivery, once again with plenty of variability (a standard deviation of 11 weeks). This seems relatively conservative compared to guidelines for post-pregnancy exercise, which suggest that it’s usually safe to begin exercising a few days after giving birth. But there’s probably a difference between getting out for a brisk walk and “training” of the type that elite athletes would find worthwhile to record in their logs.

So how did their return to running work out? Exactly half of them dealt with postpartum injury, encompassing stress fractures, tendon and ligament sprains or ruptures, and other setbacks. None of the training data predicted who did and didn’t get injured. That’s probably because the sample group was too small and diverse to pick up subtle differences, and perhaps also because the athletes were experienced enough to avoid obvious mistakes.

One statistically significant difference that did show up: among those attempting to return to elite performance, those who got injured did worse in the one to three years following the birth of their child. In fact, those who successfully avoided injury actually improved by 3.6 percent, on average, compared to their pre-pregnancy best. That’s as good a reason as any to err on the side of caution when returning to training.

It’s worth remembering that the women in this study are a rarefied group. They were already elite endurance athletes before they got pregnant, so—as with the case report published a few years ago about a 28-year-old Sherpa runner and guide who trekked to Everest Base Camp, 17,000 feet above sea level, while 31 weeks pregnant—don’t take their mileage numbers or training habits as targets for everyone. Current guidelines for the general population suggest that pregnant women should aim to be physically active most days and accumulate at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week. But if you’re used to doing a lot more than that, consider this data as your green light to—within reasonable limits and with appropriate adjustments—carry on.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.