After writing my last article about changing plans, I started to consider other times that runners are faced with training dilemmas. When nearly half of the athletes I coach at Colorado College ended up getting colds in the last couple of weeks, I realized that the common cold is one of the universal plan-destroying antagonists that runners grapple with on a regular basis. For the runners at Colorado College, this is the perfect time for colds to strike. It is that point of the track season when the training is ramping up, the temperatures stay low, and the pressures of everyday life get in the way of recovery. Trail runners and ultrarunners can end up in similar situations when the big training weeks start to add up and some of those key long runs leave our bodies tired and in need of recovery. In this article, we look into why runners tend to get sick during times of hard training, how it might be avoided, and what to do if you do come down with a cold or upper respiratory infection.

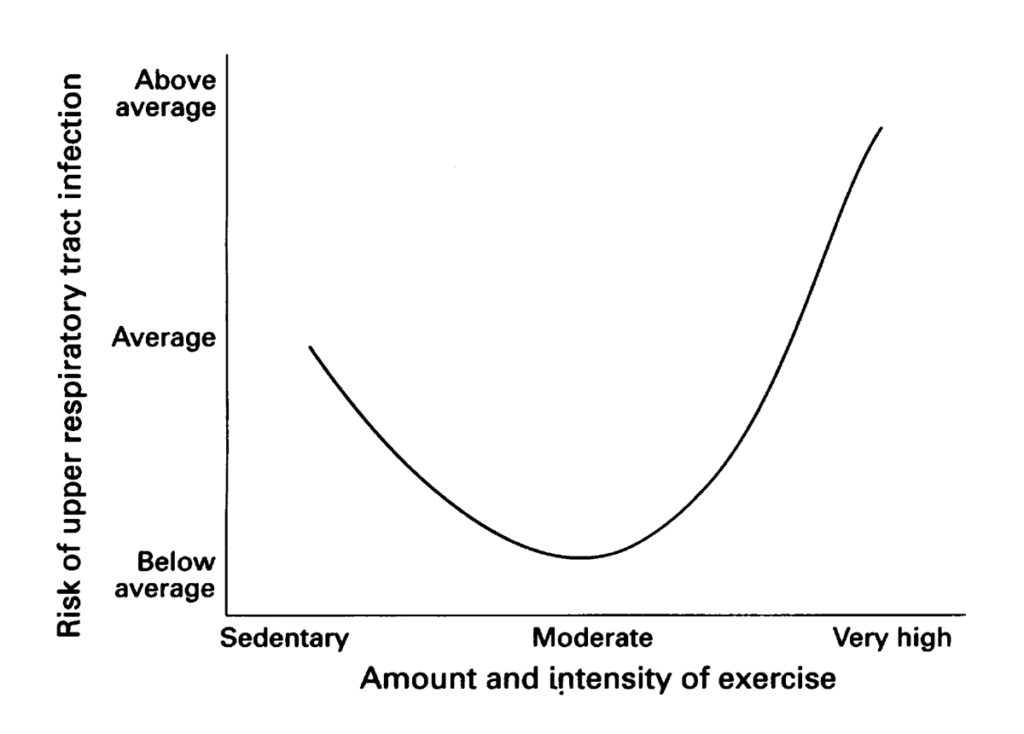

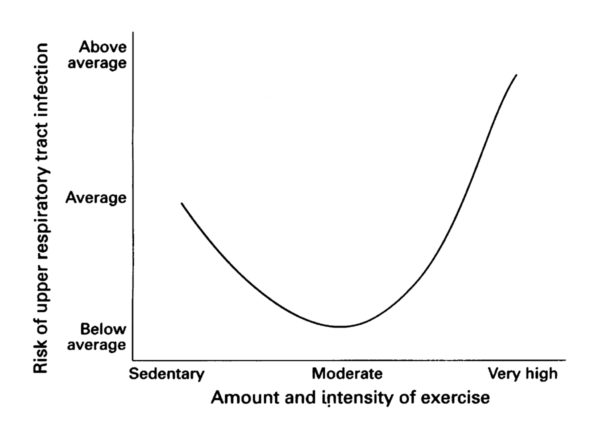

Nieman (1995) explains that the relationship between exercise and upper respiratory illness can be depicted as a J curve with the most sedentary at greatest risk of upper respiratory illnesses along with the vigorously active.

The relationship between the risk of upper respiratory infections and exercise. Image: Nieman, D. C. (1995). Upper respiratory tract infections and exercise. Thorax, 50(12), 1229–1231.

Although there is a happy medium of moderate exercise that has been shown to improve immunity, chances are the readers of this column would fall on the “vigorously active” side of the J curve and are more susceptible to upper respiratory illness. In fact, Weidner and Sevier (1996) state that running more than 25 kilometers per week (15 miles) can negatively impact an athlete’s immune system. Also, for runners recovering from a big effort like a marathon, the chance of infection increases fivefold. This increased risk can be explained by the “open window” theory (Nieman, 2007).

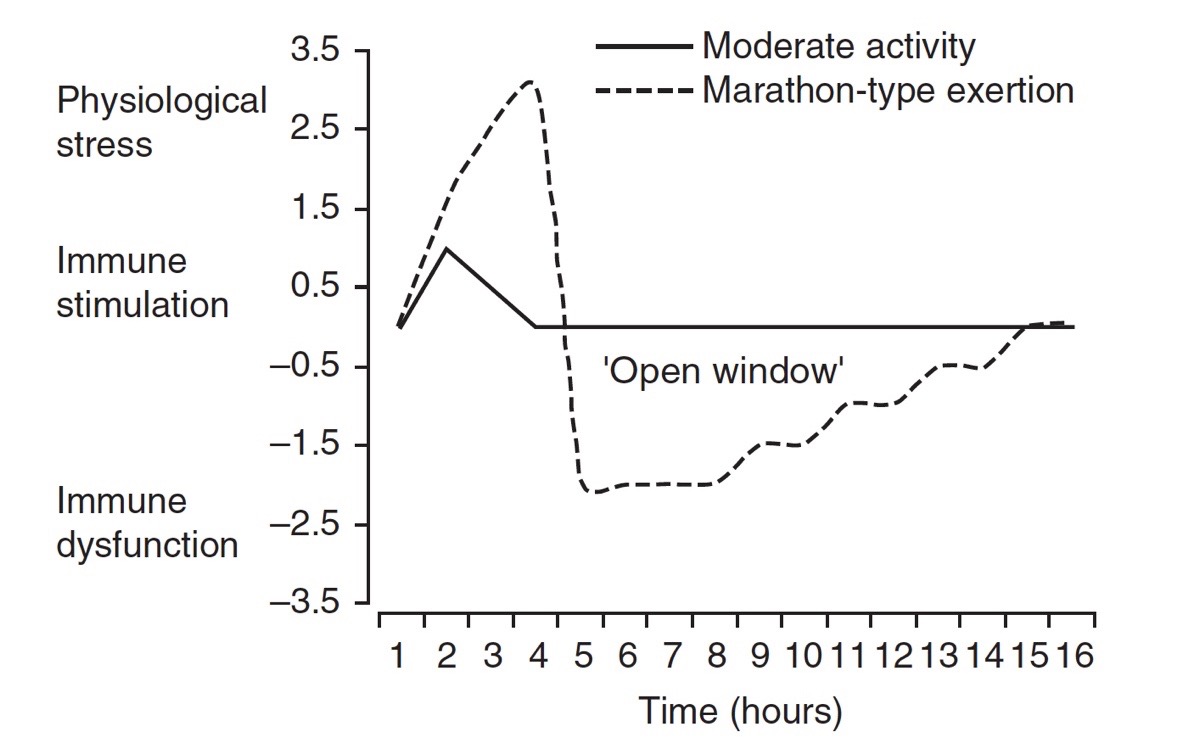

The “open window” shown as the period of time following significant physical exertion where the immune system doesn’t work normally. Image: Nieman, D. C. (2007). Marathon training and immune function. Sports Medicine, 37(4), 412–415.

The “open window” theory explains how the immune system is depressed following a hard effort. During that window, the chance of infection is greatly increased. For someone like an ultrarunner, who might even be running distances longer than a marathon in training, the risk of infection during that open window can be a real threat. When you take multiple weeks of hard training and add in the stress of long, hard workouts, it is no wonder why so many ultrarunners seem to come down with colds right before some of their biggest races. So the first question is, what can runners do to avoid getting the dreaded pre-race cold?

The obvious answer is the one you’ve probably heard before: eat a well-balanced diet, keep life stresses to a minimum, avoid overtraining, avoid sick people whenever possible, wash your hands regularly, get enough sleep, and plan your workouts and races to allow for adequate recovery (Neiman, 1995). In addition to the basics of self-care, numerous studies including work by Henson, et al. (1998) have shown that increased carbohydrate intake before, during, and after prolonged exercise can lower your risk of infection. When training for ultramarathon-type events, it is already a good practice to use your race-day nutritional strategy in training, and this evidence gives even more reason to follow that plan. Nieman (2007) points out that although carbohydrate intake has been shown to be the best nutritional countermeasure to infection, it is largely ineffective against other immune components like natural killer cell function. Natural killer cells play a major role in the way the immune system fights viral inflections. When I think about this in practical terms, it all comes down to lowering the physical stress of the training session. If a runner can get through a big workout and not feel totally dead with the help of a few extra gels, their body will be able to recover faster and minimize the “open window” to infection.

Let’s say you trained well, had solid pre- and post-run meals, ate your gels during long runs, and still ended up sick, then what? If you’ve shown signs of fever or had swollen lymph nodes, Nieman (2007) recommends waiting two to four weeks after the symptoms have improved before returning to intensive training or anything harder than an easy run. If you have less severe symptoms, like a runny nose without a fever or body aches, intensive training may be resumed just a few days after the symptoms have improved. However, when dealing with a less severe upper respiratory infection, it can be tough to know when to start training again. The key takeaway to these recommendations is that you should train through an illness if your symptoms are still present. It really just takes patience to come back correctly.

In my own experience, it has always been better to play it safe. This approach comes back to one of my core training principles: understanding that each day of training should have a purpose. If you are scheduled to do an easy run, but your heart rate is elevated and it feels harder than usual because you are dealing with a cold, then you are not accomplishing the goal. Instead, you are stressing your body more than planned. On the other hand, if you have a high-quality day scheduled and you are unable to run at the planned intensity, you are once again not benefitting from that run as you should be. So when half of the track team at Colorado College shows up sick, my advice is always going to be the same: do what you can to get healthy now because running through it is likely to prolong the inflection. I saw this situation play out last week when an athlete knew that she was developing a cold, but decided that she felt good enough to race on the weekend. Sure enough, that race made her cold worse and she was forced to take the following five days off to recover. It seems like it is especially difficult to get distance runners to back down before the situation gets dire, but the benefit of running through cold symptoms is simply not worth the risk. As hard as it is to do, my best advice is to stop worrying about the missed miles, get some rest, and get healthy as quickly as possible.

Call for Comments (from Meghan)

So, cold-season runners, how are you navigating your sick days and training goals?

References

- Henson, D., Nieman, D., Parker, J., Rainwater, M., Butterworth, D., Warren, B., Nehlsen-Cannarella, S. (1998). Carbohydrate supplementation and the lymphocyte proliferative response to long endurance running. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 19(08), 574–580.

- Nieman, D. C. (1995). Upper respiratory tract infections and exercise. Thorax, 50(12), 1229–1231.

- Nieman, D. C. (2007). Marathon training and immune function. Sports Medicine, 37(4), 412–415.

- Weidner, T. G., & Sevier, T. L. (1996). Sport, exercise, and the common cold. Journal of Athletic Training, 31(2), 154–159.