Will Pandemic-Induced Jogging Create A New Generation of Runners? – ideastream

Megan Jones has been running for years.

As a seasoned marathoner, she is a familiar sight on the streets of Cleveland’s West Side and the trails of the regional Metroparks system — often accompanied by her dog, Roxy, who pants happily alongside her.

Lately, though, they’re far from alone.

“The Metroparks have been packed sometimes,” she says. “Alarming isn’t the right word, but to a degree that there isn’t space to safe distance on some of the paths.”

Megan Jones of Cleveland with her frequent running companion, Roxy the dog, on a run through Edgewater Park. [Erin Guido]

What she’s noticing is happening everywhere. The coronavirus has turned the multibillion dollar U.S. fitness industry inside out — literally. People who typically sweat away their calories in gyms or yoga studios have taken to the streets, looking not just for a way to stay active, but to break the stale-aired monotony of home quarantine.

Sonja Persons of Garfield Heights is one of those new runners. Persons has long been a self-described fitness addict, but mostly of the indoor weight-training variety. She did her first run, a two-miler, after the pandemic closed her gym in mid-March. She plans to continue.

“[The pandemic] is making me think of other options for exercise,” Persons said. “There’s other things you can do, I’m finding, besides going to a gym and being confined inside of a place.”

With even outdoor exercise equipment off limits, people are turning to jogging to burn calories and stay sane. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

According to some observations, it may be new or casual runners like Persons — not experienced ones like Jones — who account for much of the increased popularity of the sport.

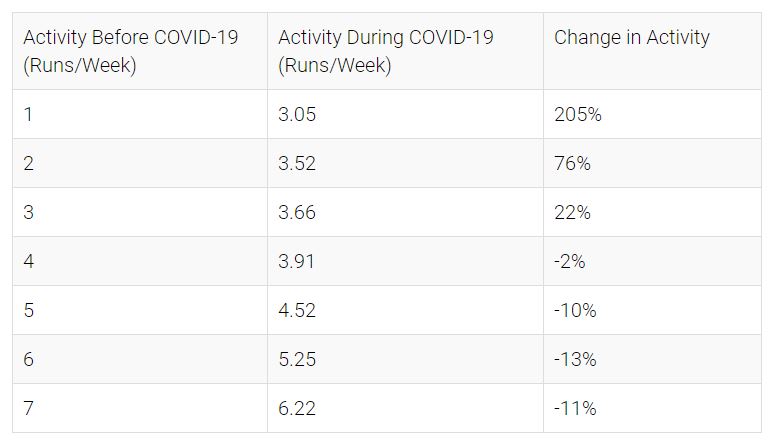

Almost 13,000 visitors to the online shoe retailer RunRepeat.com responded to an informal survey asking how they’d changed their running habits during COVID-19.

People who already ran one, two or three times a week before the pandemic all said they were running more now. The biggest increase was among those who previously ran only once a week, who now report running just over three times a week, on average.

Under COVID-19, casual runners are running more, while avid runners are actually ramping down. [RunRepeat.com]

Those who ran two or three times a week also said they’re running more. The reported reasons ranged from having more time to wanting to get fresh air during stay-at-home orders to needing exercise alternatives with gym closures.

“One of our theories is people who [typically] don’t have time to exercise a lot, work a lot,” Paul Ronto of RunRepeat.com said. “And so working from home has allowed people to get out and run.”

But interestingly, Ronto said, people who ran four or more times a week are now running less.

That’s partly because marathons and other group runs are canceled, meaning avid runners have less reason to train hard. They also reported being frustrated about the lack of elbow room on their usual routes.

“The streets are crowded,” Ronto said. “If you run on a running path, that’s crowded, to the point where we don’t think we’ll do that again.”

Social distancing standards during the pandemic have led some to become nervous about overcrowded sidewalks. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

Of course, in the age of COVID-19, more people in less space isn’t just unpleasant, it can also be dangerous. And when it comes to running, the widely accepted six-foot standard for social distancing may not be enough.

Recent research in a self-published study posits that when runners huff and puff, they create a cloud of droplets that travels as far as 16 feet behind them. But those findings are being questioned by many medical experts, including Dr. Amy Edwards, an infectious disease specialist at University Hospitals in Cleveland.

“The vast majority of those droplets are going to be large-sized droplets that will drop to the ground because of gravity pretty quickly,” Edwards said, with “pretty quickly” being a shorter distance than 16 feet.

Six feet provides enough of a buffer for runners, she said. But Edwards did caution that many people underestimate what that distance actually looks like, particularly on hiking or mutipurpose trails.

“Those trails are pretty narrow,” Edwards said. “My recommendation would be for each runner to take a step off to the side, into the grass, next to the trail.”

Balancing Safety with Health

Some fitness leaders are struggling to pass along ever-evolving advice without being discouraging, especially to those who are new to running and exercise.

Kimberly Smith-Woodford runs Cleveland-based Journey On Yonder, which organizes outdoor hikes, walks and runs for people of color.

“The information that we’re being told from the medical professionals, it’s forever changing,” Woodford-Smith said. “How safe am I out outdoors? I’m being told that I’m safe. But how safe am I in my jogging and walking my dogs?”

Kimberly Smith-Woodford (bottom right) has canceled group hikes and jogs. [Journey On Yonder]

For Smith-Woodford and other outdoor activity advocates, the current situation —infrequent exercisers working out more — would ordinarily be cause to celebrate.

Instead, she’s in the difficult situation of having to warn her networks to be careful if they do go out, and to do it alone — so she tries to include encouragement with messages about safety.

She recommends people still “get in that needed restoration or mental wind down that nature gives when we’re outdoors, but lessening the anxiety level [by running solo], because it’s just yourself and not someone else that you might be putting at risk.”

Some advocates also worry about new runners overdosing on exercise-induced endorphins.

“People are turning to running to manage stress, to get out, kind of manage that cabin fever feeling,” Jean Knaack, executive director of the Road Runners Club of America, said. “And the most important thing is not to go out too hard, too long, too fast, and it’s okay to walk.”

She recommends new runners start with walking, then graduate to combination walk-runs as they gain experience.

One thing Knaack is interested to see is whether the current uptick lasts. The number of people competing in group races has been declining since 2013, one of the many unexpected outcomes of coronavirus may be that the world ends up with a new generation of runners, she said, road-trained and ready to compete in the 5Ks and marathons of the future.